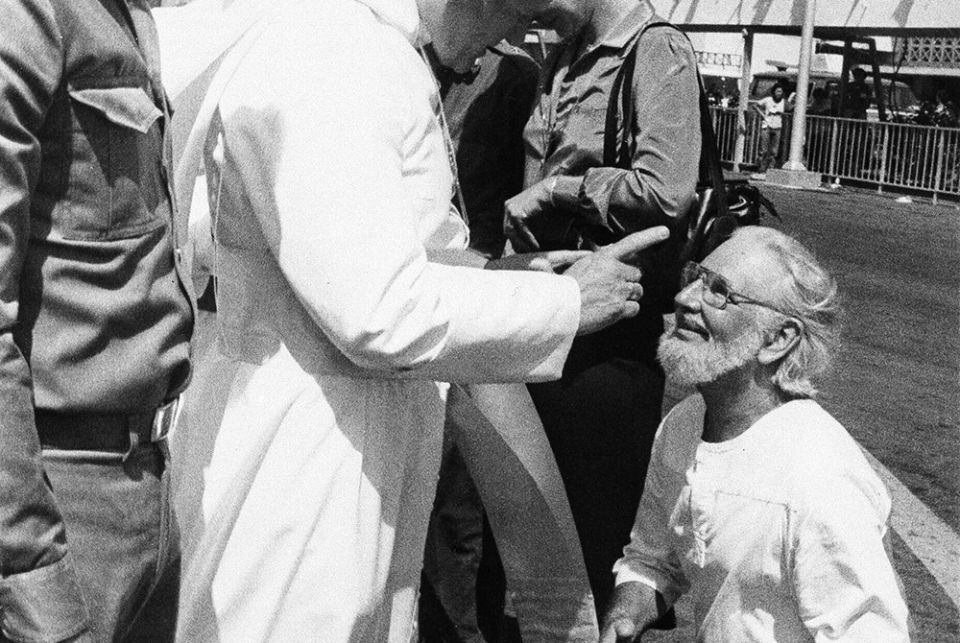

In March 1983 Pope John Paul II stood on an airport tarmac in Managua Nicaragua, shock his finger at and publicly rebuked a white-haired man kneeling before him. This moment was covered live around the world.

The man kneeling was Ernesto Cardenal, Catholic Priest, world-renowned poet and Minister for Culture in the Sandinista government of Nicaragua. He was kneeling in welcome of the Pope.

The following year Cardenal was removed from being a priest by John Paul II because he refused to quit the Sandinista government.

Only in recent days has Pope Francis “rehabilitated” Cardenal, lifting the sanctions imposed on him 37 years ago. The emissary of Pope Francis offered to concelebrate Mass with Cardenal, who is 94 years of age and dying.

Each of these men came to the tarmac of Managua from opposite poles of life and experience.

Karol Wojtyla, later John Paul II, grew up in a Poland dominated by external oppressive regimes: firstly, the Nazi German occupation wherein he studied for the priesthood in an underground seminary; secondly under Soviet communist domination, an experience which marked his whole life.

Ernesto Cardenal also grew up in a country dominated not by an external oppressive regime but by an internal oppressive regime. The oppression came not from communism but from a despotic family dynasty which ruled Nicaragua from 1936 to 1979. The Somozas accumulated extraordinary wealth through fraud, bribes, industrial monopolies, land grabbing and siphoning of foreign aid.

“Tachito” Somoza ruled in the time of Cardenal. He infamously said he did not want an educated populace, rather he wanted oxen. He literally sucked the blood from his people. He was part owner of a pharmaceutical company that collected blood plasma daily from the poor of Nicaragua for export overseas. They were paid $AUD1.50 per litre. In 1972 an earthquake virtually destroyed the capital Managua; Somoza embezzled much of the foreign aid given for the rebuilding of the city, so the city was never fully rebuilt.

Both Poland and Nicaragua were “catholic” countries. In Poland the church as institution as well as the general populace were in opposition to the communist regime. In Nicaragua the church was divided: as institution it supported Somoza, but most of the peasants and poor did not. In 1950 Archbishop Jose Antonio Lezcano conducted the marriage of Somoza in the Managua cathedral with 4,000 guests in an extravagant event. It was not until some 25 years later that bishops began to find a voice to protest the violence of his regime.

John Paul II has been credited as the inspiration behind the fall of communism in Poland and in later years across Eastern Europe. This was because of his vocal support for Lech Walesa and the Solidarity movement.

It was his experience of communism in his homeland that nurtured in John Paul II a total opposition toward anything associated in any way with communism or Marxist principles.

Ernesto Cardenal was born into an upper-class family in Nicaragua, but he left behind a privileged life to live among the peasants. Together with his brother Fernando he was ordained to the priesthood as his way of participating in the long struggle against the Somoza regime and bring about a measure of justice in the country for the people.

John Paul II had the support of most of the world in his opposition to communism, especially in the United States with President Ronald Reagan his staunch supporter.

In reverse, in Nicaragua the western world supported the Somoza regime against the Sandinista struggle, and therefore blacklisted people like the Cardenals who chose to side with the majority poor. The United States under Ronald Reagan trained and funded the infamous Contras who used terror tactics against the people. When the US Congress passed legislation to ban such support, Vice-President Bush (former CIA director) facilitated illegal sales of weapons to Iran via Israel as a means of continuing the funding of the Contras. Hence the so-called Contra Affair with retired Marine Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North initially being convicted; consequently, all convictions were reversed and charges dismissed.

John Paul II strode across the world during his 27 years papacy, visiting 129 countries and becoming one of the most travelled world leaders in history. He was enormously popular, drawing huge crowds wherever he went. He was forceful and effectively used the power that was his to command.

Cardenal is one of Nicaragua’s most prestigious authors. His works have been translated into 20 languages and he has been awarded the Legion of Honour order in the Official Degree of the Government of France. Uruguay named him the winner of the Mario Benedetti International Prize. The Iberoamerican Poetry Awards Pablo Neruda (2009) and the Reina Sofía Ibero-American Poetry Prize (2012) are among the other important awards he has received.

Cardenal was no rabble-rousing revolutionary. Following his ordination in 1965 he moved to the Solentiname Islands in the middle of Lake Nicaragua, a place of great tropical beauty where artists – painters and woodcarvers – live with farmers and fishermen. In this place Cardenal founded a semi-monastic community with the peasants: from this experience came the renowned book “The Gospel of Solentiname”, a collection of gospel reflections which addressed issues such as class conflict and government suppression. They read the scriptures in the light of Jesus’ option for the poor and the integral need of justice in His kingdom on earth.

During the escalating civil war, the community of Solentiname was burned to the ground by Somoza’s National Guard and Cardenal escaped to Costa Rica.

The theology of Solentiname was an expression of so-called Liberation Theology. It was this that drew the ire of John Paul II. And together with him, Cardinal Ratzinger, Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, who banned all teaching of Liberation Theology. Ratzinger would succeed John Paul II as Pope Benedict XVI.

Liberation Theology arose specifically in (Third World) countries which were predominately catholic, colonised by Spain and/or Portugal, where the catholic church was an institution integral to the society, but also where there was a profound gap between the majority poor (the oppressed) and the minority who were massively wealthy, including Church hierarchy. Such theology is based on the premise that the oppressed are not objects of salvation, but subjects. Meaning, they are participants in the establishment of the kingdom of God, not just in heaven but on earth, and theology is “done” from their perspective, not as something imposed. There is an element of Marxist dialects interwoven, seeking to understand the roots of radical injustice so structurally evident in these countries.

Hence the call not just for personal holiness, but for a reform of social structures that currently disenfranchise the majority. Politics and economics become integral to Christian religion.

No other Christian theology has satisfactorily addressed the issues of radical social injustice where the resources of the earth, as well as opportunities for education and participation in society, are structurally held in the hands of a few elite while the majority poor are trampled on or in a more benign setting, abandoned to eking out an elementary existence.

John Paul II was a very political pope. He moved adroitly across the political landscape as he helped dismantle the Iron Curtain. He spoke strongly against apartheid in South Africa, confronted the United States on the issue of capital punishment, promoted debt forgiveness and mediated in the dispute between Argentina and Chile. John Paul II issued an enormous amount of teaching about social justice, the reality of injustice and inequality, the need to change society. Yet he never spoke about how to reform structures of injustice, never put forward a methodology that would facilitate change. The methodology of Lech Walesa and the Solidarity movement managed to avoid state violence, but that was a rare case.

Returning to the tarmac of Managua in March 1983, the public action of John Paul II against Cardenal was brutal. There was no respect shown for a man who had stood by his people while the world stood against them, who had been a faithful servant of God though using an unusual path.

Catholic law is clear that a cleric cannot be a member of a government, but in another age with another pope that might be negotiated under special circumstances. Or in this case, should have been dealt with behind closed doors. What could not be negotiated with John Paul II – and Cardinal Ratzinger – was the disobedience of Cardenal, he had refused to submit to papal authority. John Paul II lived a theology wherein papal authority was the ultimate guiding law and could not be compromised. The fact that Cardenal was engaging in a very different theology inflamed the matter because it reeked of communism and John Paul II was unable to deal with nuances. He was so angry with Cardenal and that anger was on display.

As it happened, Cardenal ceased participating as a minister in the Sandinista government in 1987. Why did it take 33 years from that date for him to be re-instated?

It was reported that the 94-year-old smiled when he was informed of his reinstatement as a priest. We have no understanding of how to interpret this response. Perhaps, after all, it had no meaning for him. Perhaps it became something of a deathbed conversion and it filled him with new grace.

Knowing just a little of this man Ernesto Cardenal, and his history, it could be said that he was a priest all his life. While his priesthood came originally from the authority in Rome, it continued forever to come from the authority of God working through his people.

Perhaps the day will come after his death when Ernesto will be declared a Saint of the Holy Roman Catholic Church. In this most unlikely of event, would he share a cup of wine with the popes who thought they ousted him from that Church?