Anak dagat

Can you really study theology while living in a fishing village, in a small hut of four rooms, sleeping on mats, sitting cross-legged taking your meals, cooking on a charcoal burner outside the hut? Such was the situation of four young men studying to be Redemptorists when I visited them in barrio Anak Dagat (literally, Child of the Sea) in Batangas Province, Philippines. They were living in the same environment as the fishing families scattered along the beach. The only concession they allowed themselves was the use of toilets and showers in a “proper house” across from the beach.

Their purpose was to do theology from the perspective of the struggling poor. God-talk and philosophical discussion took on a different colour in Anak Dagat during typhoon months when the sea surged and the fish were hard to catch. They were living there for a month, visited regularly by a facilitator who processed with them the learnings from their experience.

They would then return to Manila, to a classroom environment, and do further studies by reading and through lectures. The students would be able to return to the same area or to be immersed within other similar communities of people. The process was driven by the need to allow faith and spirituality – as well as theology and mission – to be instructed by the reality of the poor, and by the reality of the poor who were taking the option of speaking out for themselves, taking action on their own behalf.

Our formation team had collaborated for a considerable time with other religious groups to establish a new way of doing theology. It was a triumph of sorts of creativity over normality and at that stage we were not to know how it would all turn out … There was a freshness in studying beyond the confines of high walls and libraries isolated from the living.

I spent a day and night with these guys, shared a Eucharist with them of bread and wine as well as a meal of fresh fish with rice. We swapped stories and laughed about the jar of vegemite sitting lonely on the wall. A visitor from Australia had gifted it to them and they were grateful. But they never ate any more beyond the first taste.

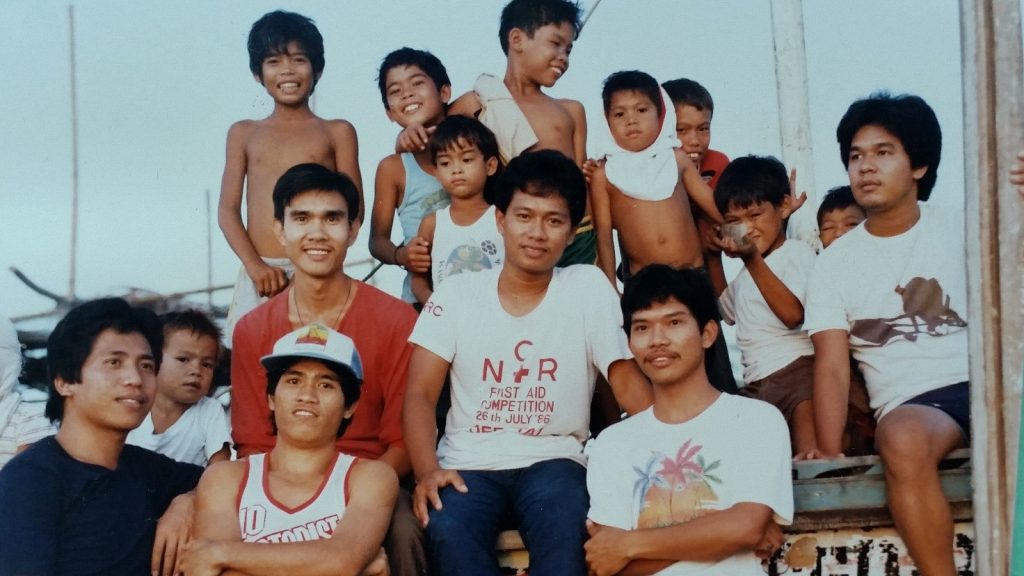

Cris, Ollie, Tito, Renato, Marlo, Meynard (RIP)

Crisanto (Boy) Domingo participated in that common journey, sharing the life of a community struggling to provide for their families as fishermen as well as sugar cane cutters.

We were in postulancy in 1986. We were in search of a Redemptorist formand (seminarian) identity as we journeyed with the struggling people. The formation program was trying new models and the “anakdagat community” was an attempt to create an action-reflection-action model of formation. We also used the term “contextualization” of formation.

Each formand was “inserted” in a basic community of farmers or fisherman and participated in community activities like farming, fishing, meetings, mobilizations, etc. I was assigned in Quisumbing, Calaca, Batangas, a community of fishermen and sugarcane cutters. It was located near a coal-fired thermal power plant. I experienced harvesting sugarcanes with Ka Fredo and catching “semilya ng bangus,” (fish eggs) with Ka Paeng which were sold to fishpond owners.

From time to time, our group gathered in Sitio Anakdagat, Barangay Poblacion, Lemery, Batangas to share our reflections on the meaning of being Christian in the context of the peoples’ life, struggles, and dreams. Part of these reflections was the processing of fears, biases, childhood issues that may affect our involvement with the people; we wanted to develop a sense of being one with the people.

During that time, I was also involved with the basic Christian communities. As I lived with the people, I was also struggling with my faith. “Have I lost my faith?” was the question that I always asked myself that time. But these “struggles with my faith” did not prevent me from becoming more involved with the struggles of the people. In the process, the prayers of the people became my prayers.

I still remember the day I joined Ka Fredo harvesting sugar cane. From morning until sunset, with bolo in hand, I swung like a machine at the cane. I purposely did not wear long sleeves to expose my arms and let the sharp edges of the leaves cut my skin. As my sweat drenched the cuts, I felt a burning sensation of itchiness all over my arms. When we finished cutting, we carried the cane on our shoulders, climbed a ladder and hauled the cane inside a truck. At dusk, I did not have the strength to stand, muscles ached all over my body, my hands were full of blisters. Cutting sugar cane was, physically, the hardest thing I did in my life. That night, I was too tired to pray, or perhaps too angry with God. Though my body was dead tired I could not put myself to sleep, my spirit was awake the whole night.

“How could a loving God allow these people to suffer like this?”

This experience led me to a crisis of faith. I could no longer say my usual prayers. Inside the church, I could only sit and look at the cross in silence.

There were a few times when I joined the people in mobilizations. We were protesting the construction of a coal-fired thermal power plant near their community. The plant supplied much-needed electric power to Metro-Manila. But it also emitted heat that drove away fish from the shoreline. When it rained, smoke from burning coal caused “acid rain” to fall on the area. Water from the underground became unsafe for drinking. Children were affected with skin diseases. So, the people were asking the government to suspend the operation of the plant and study its impact on the environment, livelihood and health of the people. But their cries fell on deaf ears, the coal plant operation continued which caused more suffering to the people.

The day I lost my faith, God became so real to me. I no longer expected that my prayers will be answered. I was not even certain if they ever reached God. What was certain to me is the belief that God is among those who suffer. And when I help those who suffer, God will become real to them, too.

early morning anak dagat

Baby crying in the house next door

Hungry sick or both

Old man shuffles by on crippled leg

Thump of hand pump delivering life

From the earth

Mother cooking rice over charcoal fire

Boy gathering shells on the beach

Hoping for a meal today

Surrounded by crashing surf

Breaking waves

Speaks to me of restless stirring

Hidden surging

Thump of wooden mallet on hard wood

Weathered wizened men already at work on another banca

Wind whistling among myriad nipa huts

Thrown together like driftwood

On the edge of life

Crying this morning as yesterday

And all days before with the pain

Of life survival in these typhoon months

When the turbulent seas refuse to surrender fish

And the boats pile up on the shore

Like orphaned ghosts

The baby has stopped crying

A child plays with an old tin can

A pregnant mother walks by

The thud of hammer and adze seems louder

Voices drift by on the restless wind

The hope of a new tomorrow

Shortly I will sit with my companions

Who taste the salt of the peoples’ life each day

We shall share our dreams

Not from the stars

But from the surging of life

In Anak Dagat Calaca Quisumbing

San Isidro Marinduque

Dare we pay the price

To see our dreams come true

August 1986