The town of Santa Magdalena lies between Bulusan and Matnog in the southern part of the Sorsogon Province of the Philippines, which in turn lies at the southern tip of the main island of Luzon. The three towns front the San Berdanino Strait, ultimately a connector between the Pacific and Indian Oceans, with its powerful tides and swirls of ocean power.

We were dropped off at the Parish Centre of Santa Magdalena and informed that because of a bridge collapse we would need to walk the 10 kilometres or so to reach our destination, the barrio of Talaonga, halfway to Bulusan town. On future entries and exits from Talaonga we rode a motorised banka, outrigger boat. This was before Holy Week and Easter in 1977, when I accompanied Fr Rey Culaba (my then mentor in all things Filipino) for a Church Mission to the barrio/village.

These were times when each day was a new learning experience for me. I had been in the Philippines for two years but still accustoming to a new language, new environment, new culture and customs. As we began our long trek to Talaonga with many locals helping with our equipment I had a sense of being far from the centre of the world, not so much isolated, as removed from the action. Yet in that then remote place I was surprised by the discovery of something quite unique: the way the people of Talaonga celebrated Easter. There were no resident priests/ministers, yet they used symbols to celebrate rituals passed down through generations; while myself and Fr Rey were participants, we were not the leaders, the liturgy came from the people.

It was like a gardener discovering to their great surprise, a new and beautiful plant in an area totally unexpected.

The photos tell the story.

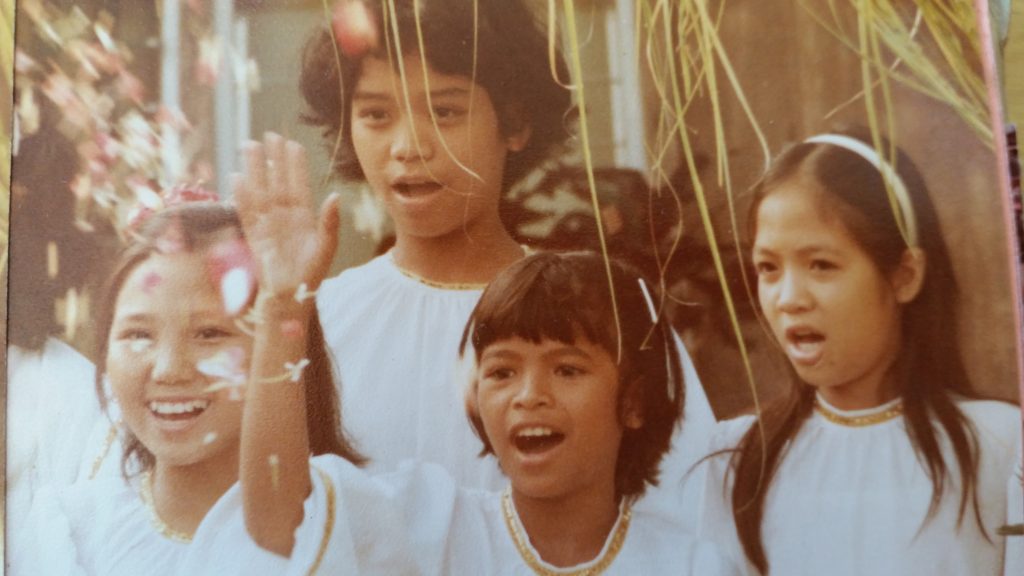

The whole barrio turned out on Palm Sunday, the Sunday prior to Easter Sunday. Using native plants and products for the colourful celebration, the Story of Jesus was sung beautifully by choirs of girls dressed in white and assembled on platforms at various sectors of the barrio.

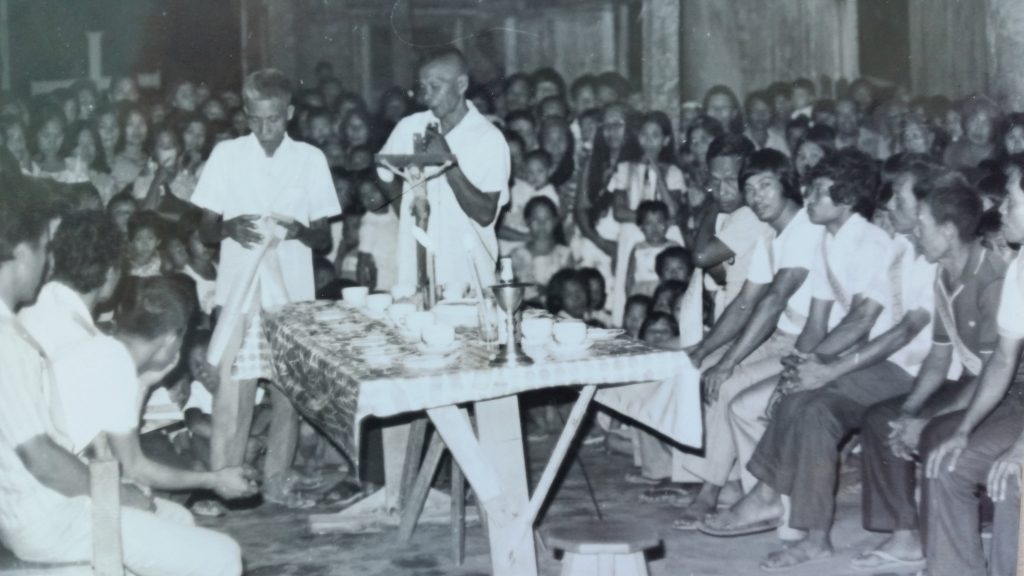

The second ritual was somber, suitably captured in black and white photos. In a dim and dark meeting hall – there was no electricity in Talaonga – the story of the last days of Jesus was intoned in chanting form, finalizing in the story of the Last Supper. It was an old ritual; it was a long ritual in a very hot and crowded place. But it was their ritual and the place was packed and silent.

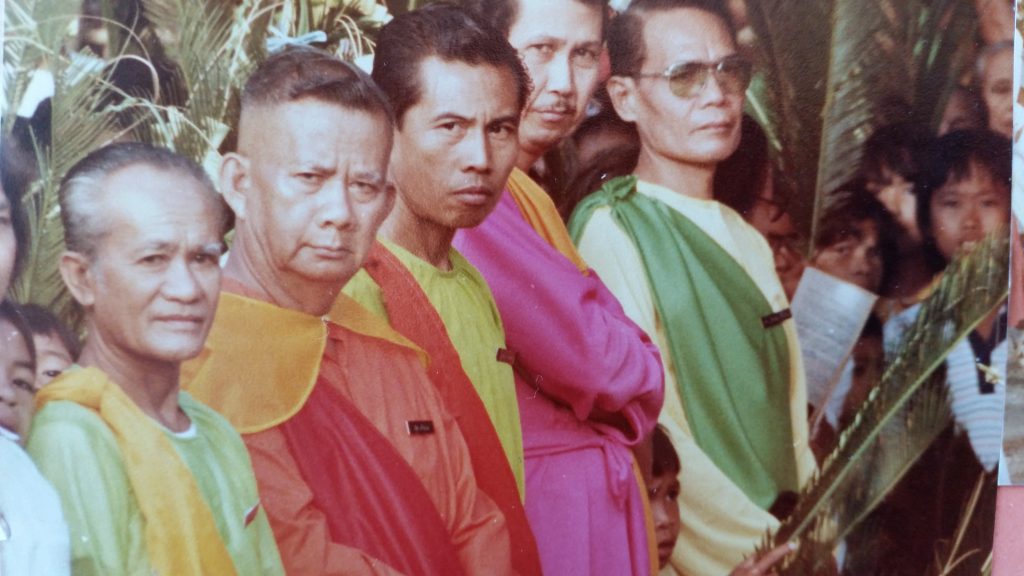

Some five years later I was on mission for 3 months in the town of Bacon, also within the Sorsogon Province, and experienced something very similar over the Holy Week period. The photos also show the celebration of Palm Sunday with the parade of palms, the singing of choir girls in their white garments standing on raised platforms; further, there was the spreading of garments on the ground for Jesus to walk upon, together with the attending disciples in colorful dress. The Parish Priest was a participant, however the liturgy – again – came from the people as a ritual handed down over centuries.

In 2017 I revisited Bacon, but found to my dismay that over the intervening 35 years, such rituals had become “unknown”, the beautiful plant that had fascinated the gardener had been allowed to wilt and die. The people in the Parish Centre were excited by the photos I had taken so many years ago and requested copies, for there were no visible records to be found in the Parish such that the memory of those events had faded and the practice ceased.

What I experienced in places like Talaonga and Bacon taught me a great deal about symbols and ritual which is another word for liturgy in the Church context.

It taught me that liturgy cries out for creativity and thrives on the use of symbols which arise from within the experience of peoples and therefore speak deeply to our spirit as well as mind and heart, opening us to ourselves, our neighbour and therefore our God.

Good liturgy does not always demand the elaborate use of words, whether by way of vocal prayers, readings, songs or sermons.

Good liturgy does not always arise from symbols imposed from above, that is from the canons of a cleric-centred church that is if often an expression of the need for control. There are symbols in life which can be released in creative ways to express our faith, our thirst for hope, our longing for resilience in the face of trauma and our need for each other in community. We can release these symbols for creative use outside the strict administration of sacraments by clergy.

A sign gives you a name. A symbol tells a story. Doctrine tells us about the Christ. Symbol tells the Story of Jesus. Doctrine informs us. Symbol engages, enlightens and enlivens us, is a catalyst for energy and commitment for the good work of the kingdom.

I undertook mission activity for eight years – together with my colleagues – away from the central towns and cities of the Bicol Provinces of the Philippines. We were invited to work in places less travelled. A fundamental experience was the receptiveness, the openness of the people to symbol and silence. The use of the basic symbols of fire, ash, water, oil, music and silence: these are the symbols of their everyday life as well as the symbols of Christian faith through the sacraments. The use of these symbols need not be confined to the formal celebration of sacraments, they can be used in any context where creativity can be allowed to express itself.

Following those years in the rural areas of the Philippines, I was assigned to very different work in Manila, assisting in the formation of seminarians who sought to participate in our ministry. This was in the years of Martial Law under President Marcos, with the level of state violence escalating and the voices of the populace rising in protest against the injustices.

How should the institutional church respond in a predominately catholic country to the violence of the state? How should church people respond both individually and particularly as small communities? At that time there was active coordination among formators of other religious groups or congregations – both men and women – as well as groups of lay people, seeking an answer to these questions. There was a common search for a revitalised spirituality that would respond integrally to the struggle of the people for justice.

There was a specific focus on Christian Symbols.

This was a major work given that in the Philippines – unlike in Australia – popular religiosity was at the heart of culture: every activity, workplace, industry, barrio, town, city and metropolis had its accompanying religious and piety expression. We sought to discover to what extent and in what ways did these expressions of faith help or hinder the desperate striving for justice among all sectors of the society: farmers, fishermen, urban poor, students, the health sector, academia, factory workers and so on.

We brought together a large gathering of church people and basically workshopped the predominant Christian symbols: Stations of the Cross, Novenas, Rosary, Processions, use of icons, images and statues and the like. Respecting these particular common symbols, small groups re-constructed or re-formulated them so they would carry the Story of a Jesus who accompanied and guided the people in their struggle. The symbols were adjusted to the particular context instead of standing apart and separate from the real situation of people. It was an enlivening and liberating experience and became the backbone of church advocacy work on behalf of the struggling poor.

A symbol of celebration and angst in the catholic church is that of Penance or Confession.

The communal celebration of penance is a powerful catalyst within any Christian community. Our sinning is an act against the community. When we lie, when we act dishonestly, when we express anger in any manner, when we fail to do good, when we neglect our obligation: in all these ways we act against others, we sin against another person or persons. Of its very nature therefore, repentance and forgiveness must be enacted within the community. When it is, there is a movement among those participating: it is a cleansing, a healing, a coming to wholeness, a movement across the community like waves upon the shore.

Such a community action in the name of the Father, is a life-giving symbol.

Amid the many noted failures of the institutional Church since the Second Vatican Council, there was experienced a particular act of resurrection: the bringing to life again of a true Christian Symbol: the communal penitential service. The Third Rite as it was so lazily labelled. This symbol was recognised, welcomed and participated in by faith communities around the world.

It defies belief then that this symbol, this sacrament, this ritual, was taken away from the community. It was an act of desecration by ecclesiastics totally out of touch with the people, an expression of clerical power that damaged the community and continues to haunt the institutional church.

In any secular society, symbols arise or emerge out of the common experience of the populace. Over a period of time they will be tested, there is a process of recognition, acceptance and celebration (usage) of these symbols. Over a long period some symbols will no longer be recognised, either because of neglect or a change in conditions of the society. Such was the case within the churches of Bacon and Talaonga.

At other times symbols will be recognised by one sector of society, but disputed by another sector. So, symbols can be divisive, or more accurately, express division. Example the use of the word “mask” in the United States right now: the simple medical mask has become a fiery symbol of division between Trump and Biden. Example the” inadvertent” posting by chef Pete Evans of a Neo-Nazi symbol on social media and consequently having his new book withdrawn from selling outlets.

As it is with the church: usage of symbols is at the very heart of ritual or liturgy. Some symbols are irreplaceable, however they can be interpreted and expressed in different ways. Other symbols may lose meaning over a long period of time or from generation to generation. Symbols cannot be legislated and then enforced for all time in the same way. By their very nature, symbols are, they exist within society and within the Christian community, even though at times they are hidden or not fully recognised.

Symbols are never static: so it is the work of artists, poets and people responsive to the Spirit of God and the Spirit of the people, to fan the flames, bring to life new symbols for testing and recognition as well as resurrect with enhanced meaning old symbols which may have fallen out of usage or no longer relate a valid story of the people. At times this process can be messy, with the future struggling to evolve from the past to create a better humanity. Or a church more responsive to the needs of people.

Symbols cannot be suppressed or contained within legislation – whether that be government legislation or ecclesial legislation. Speaking directly about church, an essential dynamic is the radical participation of people in the process of liturgy, not by taking a vote on particular issues, but by being allowed to have a voice, to be part of the designing of how to celebrate the symbol.

Lastly, in allowing liturgy to thrive in our community, as in our family, we need to deal with the burden-upon-our-Christian-backs that we have inherited from ancient Greek philosophy that permeated so much of traditional church thinking and doctrine; that is, the division between the profane and the sacred, the secular and the holy. In Christ, all reality is made whole and sanctified, there is no division, all life is one.

The universality of sharing a meal always symbolises peace and harmony. The gathering of a community to celebrate through the breaking of bread and sharing a glass of wine is a constant witness to the dying wish of Jesus to”Do this in memory of me.” The host or hostess of the moment should be the one to invite us and be the chosen” head of the table” for any particular meal. No need for clerical cast to be leader of the gathering.