This account was written on May 18 1998, a year after Dad passed away.

It is a very hard story. It touches the heart of our family, but it can also be the story of every family, a human story of struggle with the pain and grief of a couple who loved each other so much for so long, but were unable to manage the insidious workings of dementia in their last years. This is the reason I make the story public.

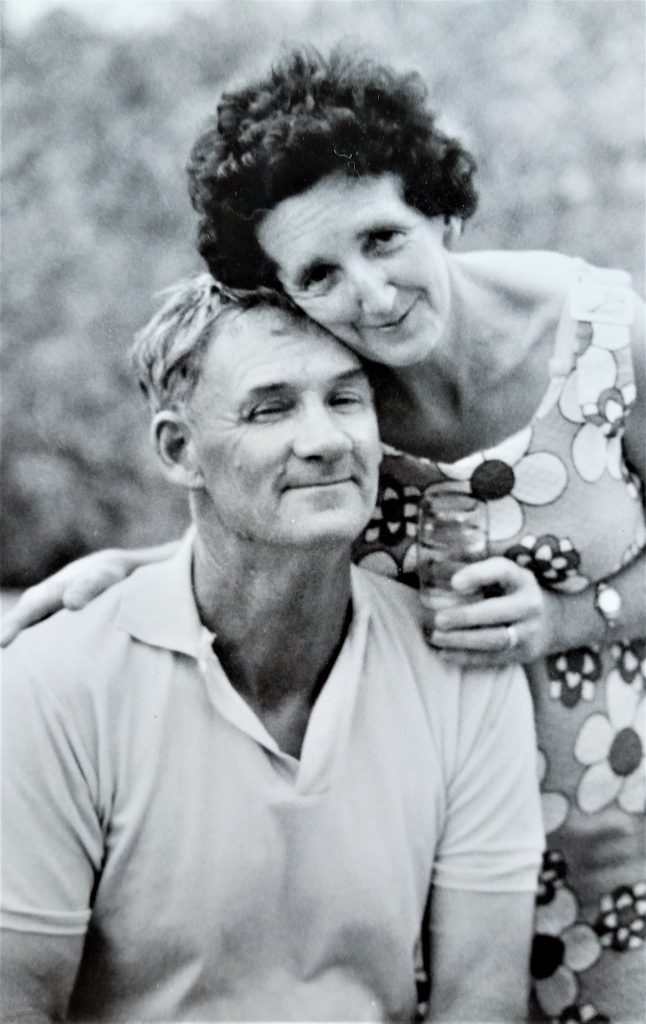

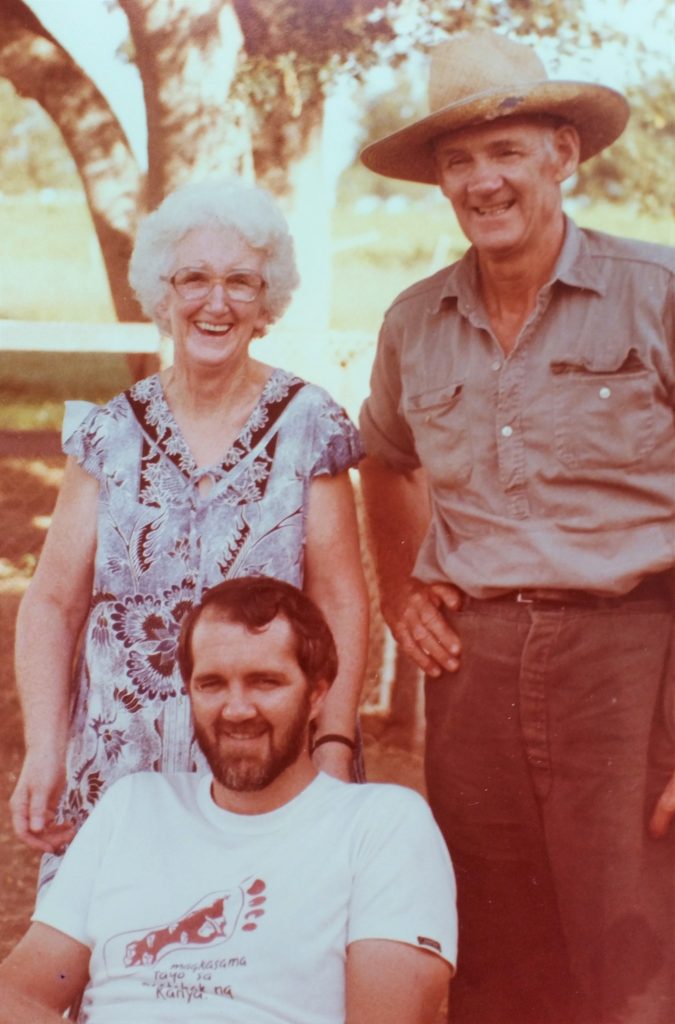

The story is a recognition of Dad and Mum’s deep love for each other; it is also a recognition of their frailty, and of how all of us brothers and sisters were caught up in the whirlwind of trauma. As a family we continue to reflect upon and recount stories from Dad and Mum’s last five years together.

In 1993 Mum and Dad travelled from their hometown of Biloela in Central Queensland to Newcastle for the funeral of Mum’s sister, Aunty Kath. However, on the day of the funeral Mum refused to attend. This meant that Dad did not attend either. Later, Mum’s mood changed and she was angry at Dad, blaming him in particular for not forcing her to attend.

It also happened that while they were in Newcastle, family members encouraged Dad to take the opportunity of continuing south to visit his family and friends around Howlong in southern New South Wales, the place of his origins. Twice before since their retirement Dad had sought to make this trip and twice it never eventuated because Mum either refused or was unable to go. We felt the opportunity would not present itself again, so we offered to help in the exercise which help included one of us being prepared to travel down to stay with Mum in the meantime. But Mum did not want Dad to go and Dad could not or would not seize the moment.

A year earlier than this incident, in 1992 and five long years before Dad was to pass away, Mum underwent a multitude of medical tests in Brisbane to determine the source of her “condition”, which condition included, among other things, tiredness, inertia and forgetfulness. The extensive tests proved negative, but the physician mentioned the words Alzheimer’s and Dementia. Nothing really came of the exercise except that around that time Mum and Dad began attending regular meetings in Rockhampton of the Chronic Fatigue Society.

The incidents above symbolise the struggle and pain of the family, in particular the pain that encompassed Dad’s life, over the next five years until Dad’s death on April 21, 1977.

There were three main elements in the long and painful struggle, to which people outside the family were not witness to. These three elements are highlighted in the incidents related above.

- Mum’s deteriorating situation and its demands upon Dad.

The story of Aunty Kath’s funeral shows how, even at the relatively early stage, Mum’s behaviour and moods were becoming unpredictable as the grasp she had on her life began to unravel. What happened at the time caused a great deal of pain to Dad. At the same time, he allowed his own behaviour to be dictated by Mum: both in not attending the funeral and refusing the offer of going on to Howlong.

Mum’s deteriorating situation was evidenced by such things as forgetfulness and confusion, dramatic mood changes, loss of basic capabilities such as cooking and housekeeping, increasing inertia, compulsive repetitive behaviour, inability and reluctance to mix socially and developing total dependence upon Dad.

It came to the point that Dad could hardly go anywhere on his own, as Mum would be afraid to be on her own. She could not function without Dad present, so unsure was she of herself. On the other hand, Dad could not go out if Mum did not want to go and as time progressed, she desired to go out less and less.

At the weekly St Vinnies meeting Mum would gladly volunteer their services to do home visits, but when it came to actually do the visitation she did not want to go, which left Dad in a very embarrassing situation. A number of times he said he would resign from St Vinnies because of the situation. How many times did we hear the story from Dad: “Mum complains that she is a prisoner in the house because she is unable to drive and has to depend on me to drive her. But I tell her ‘No, I am the prisoner in the house because if you do not want to go somewhere, I have to stay at home, but anytime you want to go somewhere I am able to take you.’”

If Dad went next door or across the road to talk to Col or inspect the building of the new house, Mum would go looking for him, angry and shouting across the road for him to come home. If he went down the street for a while and was longer in returning than expected, on his return he would be shouted at, Mum would slam the door and go into the bedroom as a way of punishing Dad. Later there would be either the remorse when Mum felt guilty and cried for her behaviour. Or she would simply forget what happened and act as if nothing happened. Meanwhile Dad would be hurt and confused.

Shopping became a real trial, so that eventually it was confined mainly to the bake shop and Johnstone’s grocery. Mum would load the trolley with items they already had or did not want, so it was the easier path not to go shopping except for the few essentials. Their diet suffered badly as they increased their consumption of pies and cakes from Simmons’ bread shop and virtually stopped cooking for themselves, except for the weekly roast which provided one hot meal and cold meat for the rest of the week. Food from Meals on Wheels was good and sustaining, but accounted for only five meals a week out of twenty-one.

As Mum’s mind lost more of its focus, as Mum forever kept losing or misplacing things, the strain on Dad increased as he found himself always on the alert as to what Mum was doing, where she put her handbag, her medicine, her glasses, her watch etc., so that when she required any item he would know where it was. In such a climate of watchfulness, relaxation became a luxury rarely experienced.

When it came to going away to Rockhampton for one night or Brisbane or Cairns for a week and they had to pack clothes, the exercise evolved into a mini trauma as Mum spread her clothes from one end of the house to the other trying to decide what to take, but being unable to decide. As Mum became more confused, so the sense of frustration increased for both of them and invariably they came away without some essential items or with very little clothing for Mum.

On the night Mum and Dad stayed at Unmack Street before leaving in the morning for Cairns, Mum completely forgot they were going anywhere and accused Dad of making decisions without consulting her. On the next morning, Mum had no idea where they were going or why and Dad vowed it would be the last time he would go anywhere with Mum.

There were times when everything went smoothly for a time and life was easier. Then a “bad time” would set in when Mum would be demanding and angry, would throw things around the house, then break down and cry, being remorseful and guilty. In these times of anguish Mum would make Dad promise never to put her into a home, never to tell anyone, even family members. Dad kept exhorting Mum to put her trust in her children, that they knew and understood what was happening and there was no need to keep secrets from them. However, Mum never adopted this attitude, choosing instead to rely totally upon Dad and not being able to be at ease unless he was within sight.

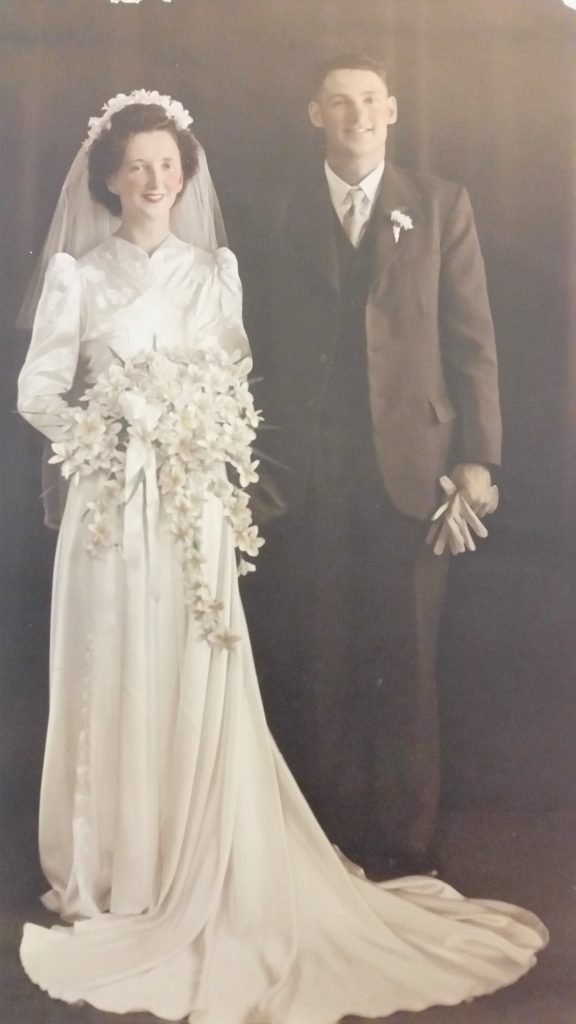

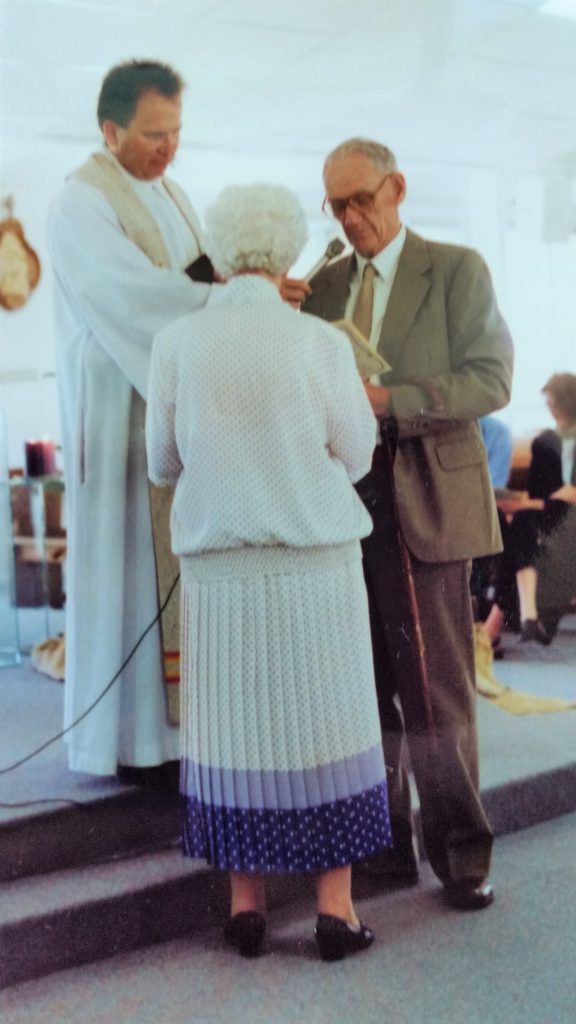

For Dad, their Golden Wedding celebration in 1994 was more of an endurance than a joy; he admitted afterwards that had it been held three months later he would not have been able to go through with it. While the ceremony itself was a joy and success, the lead up and follow on made him wonder if it was worthwhile. During the social event that evening, it was obvious to us that Mum was in a type of bewildered state, unable to appreciate what it was all about. When Mum saw Dad talking to one of their daughters after dinner, she asked “Who is that woman that Richard is talking to?”

Over the last couple of years Mum developed a particular lifestyle which was both her way of coping with the confusing world that was closing in around her and at the same time an expression of the depression she was constantly experiencing. Mum would rise late, have breakfast, go back to bed and not rise again till late morning. She would have a shower – or, as time went by, go through the motions of showering – watch some TV which she increasing failed to understand, have lunch and go back to bed. After dinner, Mum would then want to retire early and began demanding that Dad come to bed also. Eventually Dad came to imitate to a large degree this same lifestyle as he was forced to comply with Mum’s behaviour.

For the last twelve months before Mum died Dad’s life became an increasingly tortured existence. Their way of living deteriorated as he became less able to cope and took the road of doing less and less. They washed their clothes less frequently and when Mum went for a shower but did not turn the water on, he did not have the energy or will to confront the situation.

- Denial and “united front”

The tests Mum underwent in 1992 were an outcome of a concern already prevalent among us about Mum’s situation. While there was debate about the nature of causes of her condition, yet there was a clear consensus that it was not simply chronic fatigue or Ross River fever or any other such ailment. Rather it was a form of dementia or Alzheimer’s and/or the result of years of heavy medication for depression.

It was not until the end of 1996 – only a few months before he died – that Dad finally admitted to himself by admitting to us the Mum’s sickness was not just physical but a deterioration of the mind. Virtually up to the end of his life he was in a state of denial, and if he was in denial so too of course was Mum.

Furthermore, Dad and Mum developed a “united front” strategy which was dictated to a large degree by Mum. The critical element here has been referenced above, wherein Mum made Dad promise to say and do nothing. Dad did promise and the keeping of those promises was to have profound effects on his life and way he handled or mishandled Mum’s gradual deterioration. It certainly placed an enormous burden upon him, restricting him from allowing friends to assist him bear the burden, restricting him from availing of other forms of available home help and home respite. It contributed to his slowness in accepting a double unit at Wahroonga Retirement home.

At the same time, on a social level, Mum moved more and more in Dad’s shadow. This was a natural progression because Dad had always been more dominant in their social relationships, so it was not hard for him to compensate more and more for Mum in the public arena. They worked effectively, either consciously or unconsciously, so that those around them could never even begin to guess at the real situation that was unfolding behind the doors at Ward Crescent.

Effectively they erected a protective wall around their lives. Mum was very aware that “something was wrong” and from years back was fearful she would endure the same fate as her own mother, Nana, who became geriatric. Mum was unable to entrust her situation to us, was unable to share her fears. Even more so did she carefully maintain a front to non-family including close friends. Mum only met with others with Dad present and confine her comments to the weather and other neutral topics.

Dad made the decision that it was he who ultimately was to carry the burden of Mum’s deterioration; he found it very difficult to see that others could/should help him. While he would talk to us about what was happening, it was more for the purpose of getting it out of his system rather than asking for help or seriously discussing possible options.

So was developed the grand conspiracy wherein in public Mum lived in Dad’s shadow and Dad more and more compensated for her in order not to expose her true condition.

- Family members seeking to address the situation

In different ways and over the whole period of time, we as a family sought to address the situation and seek ways to ease it. This is highlighted in the story about trying to get Dad to visit Howlong: a typical attempt to help Dad “negotiate” Mum’s changing behaviour and not allow it to totally dominate and dictate his own life.

It is also highlighted in the story of the medical tests. And the story goes on, seeking the intervention of the Alzheimer’s Association and the intervention of the Aged Care Assessment Team. But the story is mostly told in the countless hours of conversation between ourselves and with Dad, with all the inherent urging, pleading, pushing for concrete action to address the situation, and finally a sense of resignation that the decision was not in our hands and ultimately, we could not take responsibility for Dad’s life.

Conversation with Dad was not easy. Initially Dad was reluctant to talk about it, sensing it was a betrayal of his promise to Mum. Eventually when he did begin to open up, and knowing that what was happening was visible to us, he talked not so much to gain solution but to gain relief.

At the same time as Mum shadowed Dad more and more closely whenever visitors were around, it became increasingly difficult to create the opportunity to talk to Dad for a long enough time; and when you did get the chance to talk to him on his own, he would talk about everything except what really mattered! This was understandable, for while we wished to talk to him about ways of caring for Mum, he had a very real need of talking with someone about something else for a change.

Our fundamental concern was to ensure as much as possible, Dad’s continuing good health so he could continue to look after Mum. One thing we were in total agreement about with Dad, was that should something happen to him by way of death or sickness, Mum would be totally lost and her life would devolve into total trauma. On a number of occasions Dad expressed hope that Mum would die first because he could carry the sorrow of life without her, but she would not be able to carry the sorrow of life without him.

As did eventually happen.

Ensuring Dad’s continuing good health meant a number of things:

Firstly, proper food and care of the household which was simple enough. It was a struggle initially to get him to accept Meals on Wheels and household help once a week, yet once in place he warmed to the experience. While these programs helped, they did not address the situation as best as we would have liked. But Dad would not move on other items such as getting someone to help with weekly shopping and cooking of other meals.

Secondly, and most urgent, it was our greatest concern to provide Dad with respite as a carer. In reality he was a 24-hour Carer. If he was not able to obtain effective and regular respite, then it would not be too long before he himself came to be in need of constant care. This was the heart of our struggle with Dad for five years, increasing in intensity as time went on.

He was eventually able to persuade Mum to attend respite care once a week for a couple of hours, but Mum did not like it, and further suggestions to Dad were not taken up.

Particularly we encouraged Dad to enlist the support and help of friends, including extended family members living nearby, to bring them “into the circle” so they could help carry the load. But he was ever adamant this would not happen; it would betray his promise to Mum.

The BIG Question: In event of Dad’s Death …?

The situation was dramatically highlighted as early as 1994 when Dad suffered a heart attack. Even at that time Mum was like a lost child, totally confused and unable to cope. The question was raised then: what would happen to Mum in event of Dad’s death?

As we witnessed Dad’s own physical deterioration before our eyes and felt powerless to help, we became more intent in creating the situation where Mum would not be abandoned in event of his death and where the trauma would be softened.

Time was running out. Up to late 1996 Dad held the view that should he die first Mum would have no option but to go and live with one of her children. He consoled himself with this thought, and so it seemed a terrible thing to tell him that such was not possible. For more than two years we agonised over this question and came to accept that we would not be able to care for Mum in any of our homes. Knowing her situation which deteriorated constantly, and her needs which increased daily, it became very clear that we simply would not be able to look after her. Mum could never be left alone and increasingly needed professional nursing care.

Knowing this, we worked against time to convince Dad to take up residence at Wahroonga Retirement Village. Our hope was twofold: firstly, Dad’s burden of care would be shared by others so that his health would not deteriorate and he would outlive Mum. Secondly, in event of Dad taking ill or breaking a leg or in the worst scenario, passing away, Mum would already be in familiar surrounds and would not have to be transferred elsewhere.

Dad finally began taking concrete steps towards putting this plan into effect, after for a long time stonewalling our attempts to convince him to move to Wahroonga for the sake of Mum. Around Christmas 1996 Mum went through two particularly bad times when life became intolerable for Dad. He could see Mum becoming more erratic and unmanageable in her behaviour, he could feel his own strength and energy ebbing. The bargaining, coaxing, urging and persuasion was almost constant from October through January. In January he gave the go-ahead to make final preparation for entry into the first married couple’s unit at Wahroonga.

Dad was always a private person, so in early March 1997 when I visited them it sent a shiver down my spine when he took me into his office and showed me “where things were”: their personal papers, bank accounts and such. There was little reference to the plan to transfer to Wahroonga. What had happened to bring about the sharing of such confidences? The lady who lived next door to Mum and Dad later shared with me that Dad had suffered a couple of minor strokes before the big one. We had not been told about those.

It happened that Mum and Dad never made it to Wahroonga and our worst nightmare for Mum suddenly became true. He knew this too; you could see from the expression of his face as he lay in intensive care in Biloela hospital before the effects of the stroke took full control. For years we had talked and argued and did everything in our power to ensure we could avoid the situation we now had to address.

There was no time left. Paul and I as attorneys had only two hours to make a decision and the decision had to be permanent. In a time of such great distress and catharsis for Mum we could not take actions which made us feel better in the short term but in fact caused further distress to Mum in the long term.

The only plus on our side was that we had been thinking and talking about this situation for more than two years since Dad’s heart attack. We knew in our minds what we had to do; we knew there was no option. In that sense, no decision had to be made. What was required rather was the courage and spiritual energy to carry out a course of action which was naturally speaking most unnatural, which was heart-breaking and felt like an act of betrayal of the person you should care for most: your own mother in her hour of greatest need and vulnerability.

It was the hardest thing I have ever had to do. That night I felt physically sick because of what Paul and I had to do, place Mum into the care of people who could look after her. Then we had to face the possibilities of Dad’s situation. The only small grace was that he lived on for a week, giving us some time to adjust to his coming death. Inside, I never doubted that he would stay with us only a short time further; he had had enough and wanted to travel on. Once we had assured him that we would look after Mum, he was happy to leave her in our care and move on to another place.

And now … 12 months later:

Life ultimately can be a tragedy at the end. Nothing we do can change the way Mum and Dad’s common life ended, in lonely separation for Mum which she cannot comprehend. Mum keeps telling us that “Richard has left me.” Words pile on words as we seek to explain WHY and HOW he left her; the words flow over her and her mind does not register. There are times when we visit her, she is so happy. Sometimes she is so sad because Richard has left her. Other times Mum is just so angry with us.

Thank you so much Tony for sharing this poignant (if at times also tragic) story of your mom & dad’s life and loves. It must’ve been very hard for you to even want to remember some very painful parts of your story; and very courageous (and generous!) of you to decide to share it all with me/others! In all the years that we have known each other, I don’t remember you sharing any of this with me: nor would I have expected it then or now, So I really feel honoured you are sharing this now.

I won’t/can’t even imagine what it all was for your mom & dad, and for the rest of your family!

I am simultaneously overwhelmed and inspired by the indomitable spirit that sustained them through such pain & suffering! Perhaps that is what I believe is what a Christian Marriage gives a man & a woman- sa hirap at ginhawa.

Indeed, Ben, a story both poignant and tragic, whose reality still (haunts us?) as in lives within us family members. How do we find meaning in the torn life of Mum’s last years?

Dad’s love for her never failed, but did his courage fail when faced with cliff-high options?

Dementia can really be a beast of an illness and is difficult to share. However I share it in the hope that it may shed some small light and insight for those who are entering upon that dark place.